A Descent into Limbo with Maurice Sendak

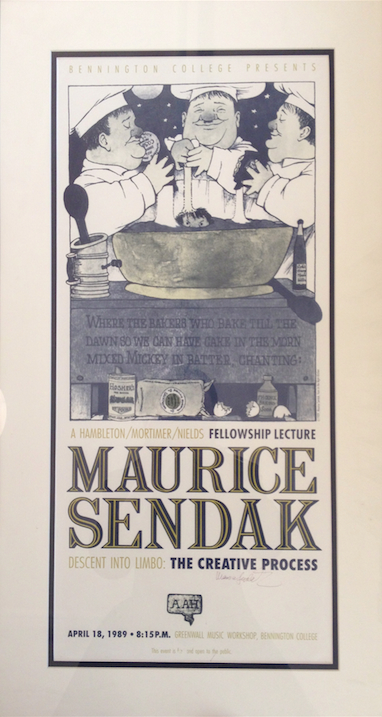

The poster for Maurice Sendak’s lecture at Bennington in 1989

We open with a Plato-like scene, allegory of the cave style (except the year is 1989 and the video quality is sub-par). Greenwall Auditorium is dark. A light softly illuminates a broad-shouldered figure with glasses perched nimbly at the edge of his face. The audience sits attentively before him. He is Maurice Sendak. And they are all waiting to be saved, in their respective ways. The quest? “Descent Into Limbo: the Creative Process.”

Sendak, widely known for writing and illustrating Where the Wild Things Are, appears before this Bennington audience quite modestly. He begins by describing a painting that inspires him. Christ, adorned with saints, looks into a “vast, gaping hole. A limbo.” And in this limbo, men are desperately looking up at Christ, waiting to be saved. “[E]ven though you can’t see him,” Sendak says, “you can tell from his shoulders and his back that he is frightened, and the sight of it is terrifying…and there’s just that moment’s pause, or at least I imagine a moment’s pause, where he hesitates.” And so, to complete the analogy, the creative process is “leaping generously into the unknown.” Christ-like.

The creative process. The phrase is honey-sweet on the tip of the tongue, but it goes down like sawdust. Many artists can’t swallow it. Hemingway. Rembrandt. Ian Curtis. To make art is to die in it. And maybe to come out the other side. Sendak knew this. And to hundreds of young minds in the audience about to leap into a world of uncertainty and impossible opportunity, he calmly imparts this wisdom: “You may not solve the creative dilemma, but you just have to have faith that you might.”

Following this introduction, Sendak recalls publishing one of his first books, Dear Mili, based on one of Wilhelm Grimm’s fairy tales. As it was inherently religious, he wasn’t attracted to the tale at first. The setting is a war-stricken village. A frantic mother sends her daughter, Mili, off into the woods to escape the conflict. There, she meets St. Joseph, the patron saint of lost children, who protects Mili until the war is over. A young (and defiantly secular) Sendak was repelled by the story’s ecclesiastic references at first. He kept living his life, performing in his first Opera in Amsterdam. Every morning, he “passed Anne Frank’s house…and I knew, happily, that she could be the model for Mili. Mili is a lost child in the war, Anne Frank is a lost child in the war.” His connection to Anne Frank translated into a new inspiration for Mili, not fueled by the story’s religious undertones, but, rather, by the sheer human ability to adapt, to survive.

In a state of vulnerability. In limbo.

Perhaps the biggest theme in Sendak’s work, he tells his audience, is the crisis in a child’s life. Of course, “the parent loves the child but does not know they are in crisis. The courage of children to survive by themselves in unexplained moments without logic, without strength, to get through.” We see this most notably in Max, the protagonist of Where the Wild Things Are. Max faces an internal struggle, which is easily and often trivialized because he’s a child. Are we not all in the midst of some sort of crisis that allows us to come out of it ultimately self-aware and better off as human beings? Are we not all hoping to reach that incendiary moment of acceptance, creation, or higher enlightenment?

For Sendak, his characters are not merely children with singular thoughts and desires. Yes, they dance, but with flowers blooming in their footsteps. And they daydream, but of wild animals as symbols of utopia. They feel just as intensely as any adult. Maybe more intensely. It’s the crisis of “seeing more than maybe you understand, or wishing to see more.” And with children’s literature in particular, “the difficulty is the assumption of what a children’s book is, which is very different from what I think a book is.”

Mistakes? “They happen quite naturally.” Creative blocks? They are inevitable. But, “you just sit it out, there is no solution. It seems to come to an end by itself. You ride, you twist, you carry on. The real anxiety is maybe, this is it. Well, there’s always that maybe …”

That is limbo. Consequently, the uncertainty is what it means to make art. And sometimes, “there’s a risk that you may not come back.” But to give yourself completely to a project is when art crosses dimensions, transcends mortality and becomes ephemeral. Devotional. Religious, even. For Sendak, religion is standing in Anne Frank’s childhood room, or looking at Van Gogh’s paintings, or listening to Mozart’s sonatas. We learn to trust somehow, just as Sendak’s books teach us. Trust in ourselves, in our art, in those who came before us and those who will come after us.

Trust that, when (and if) we do come back from the creative wilderness, the soup will still be hot.

The video of Sendak’s talk at Bennington can be found here.Followingan introduction byBennington’s former President Elizabeth Coleman, Sendak’s address starts at 5:22. His description of the painting Christ in Limbo comes at 7:55. He talks about the background for his book Dear Mili at 8:10, and about his fascination with the theme of children in hardship at 48:45. There are tips and exercises for overcoming creative block at 42:34, and again at 58:03.